Stanford study probes psychological resistance to recycled water

Stanford researchers have found that Californians’ views on recycled water depend heavily on how that water is eventually used.

The study, which appeared in the August 2017 issue of Water and Environment Journal, revealed that psychological resistance to using treated effluent can be reduced, to some extent, by explaining the treatment process to people and informing them of an existing program in Orange County.

“In short, adding positive claims boosts support for using recycled water to some degree,” according to the study, “but the public remains resistant to using water that involves ingestion or personal contact.”

The paper, based on a 2015 internet survey of 1,500 Californians, was authored by political scientists Iris Hui and Bruce Cain, who are affiliated with Stanford’s Bill Lane Center for the American West. (Full disclosure: Cain was a reader of my master’s thesis in political science at U.C. Berkeley in 1998 and I did a media fellowship at the Bill Lane Center in 2013/2014).

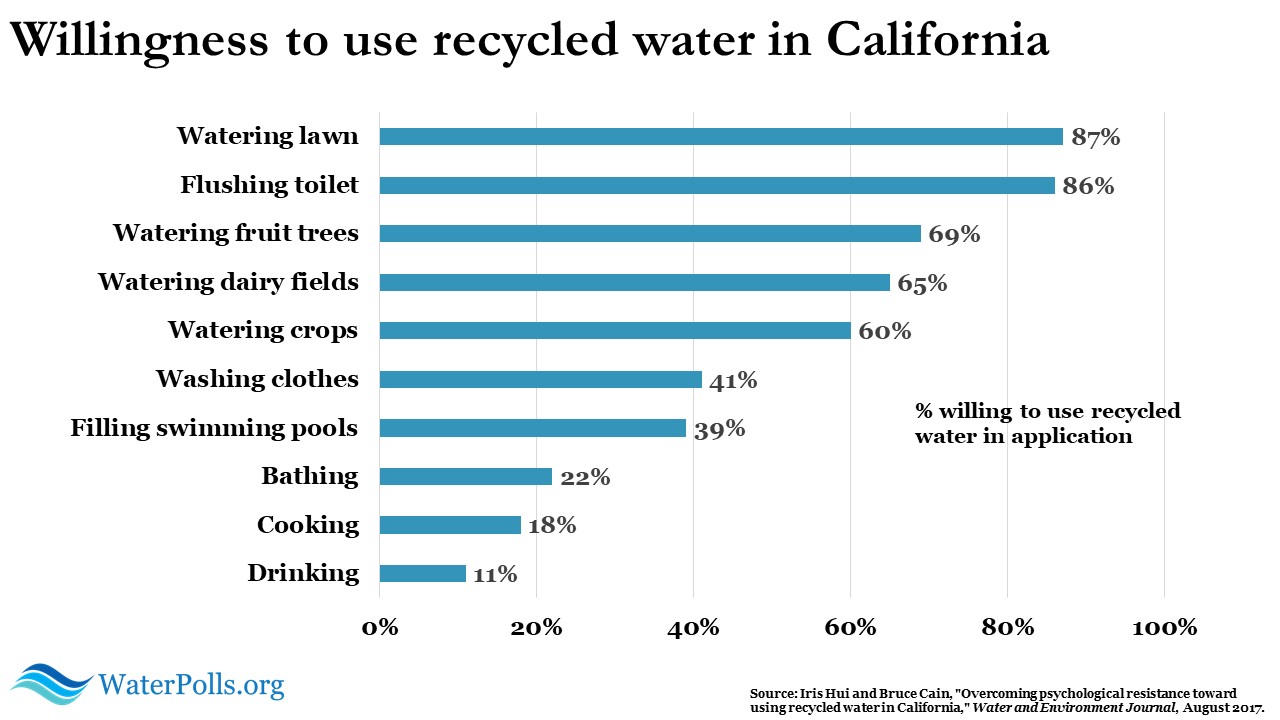

The graphic below, which I created based on the study’s data, shows that nearly 9 in 10 Californians are willing to use recycled water for watering lawns and flushing toilets. It’s a different story when it comes to skin contact or consumption. Only about 1 in 5 Californians approve of bathing in recycled water or cooking with it. Just 11% say they’re willing to drink recycled water.

Demographic differences

Analyzing social and demographic factors, Hui and Cain concluded that males are generally more willing to use recycled water than women. Self-identified Democrats are less resistant to using recycled water than Republicans or Independents. Republicans appear less willing to embrace the technology because GOP voters are three times less likely to see climate change as a serious threat, and they’re more skeptical of government attempts to regulate the water supply. “Given the psychological stigma that recycled water has for many people,” Hui and Cain write, “the willingness to overcome that inherent aversion should increase if a person believes that using recycled would serve some larger purpose such as climate change and drought adaptation.”

Looking across the state, the researchers found that support for recycled water was especially high in the Central Valley, a farming region hit hard by drought and groundwater depletion, though residents in the Central Valley also balked at drinking and cooking with recycled water.

Contrary to some previous research, Hui and Cain’s paper discovered that respondents’ educational level didn’t affect their views of recycled water. The researchers conjecture that one reason for the lack of an educational effect was the salience of California’s epic drought, which heightened awareness of the need to find new water sources. “We did the poll during the drought, so it was on the news every day,” Hui said in an interview. “Everyone was totally getting the message and understood the urgency of the problem.”

Experiment tests impact of messaging

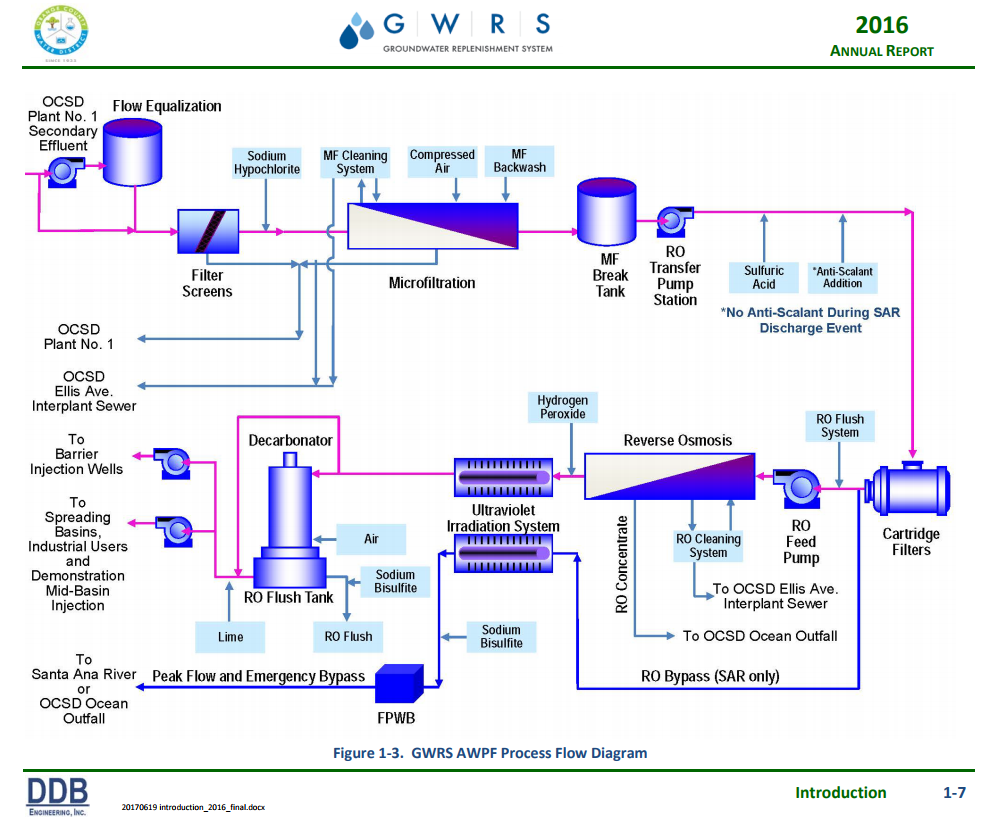

As part of the study, the researchers conducted a randomized experiment in which some people were educated about Orange County’s Groundwater Replenishment System, which the utility describes as “the world’s largest water purification system for indirect potable reuse.” The process involves taking treated wastewater that would otherwise be discharged into the Pacific Ocean and purifying it further with a three-step process before injecting the water into local groundwater aquifers.

“When we give people more information about the recycled water system and how it gets purified and injected into local groundwater before being taken out for use, those details make people feel more comfortable using it in certain applications,” Hui said. “The public information on this particular topic is very shallow. When you frame it differently, people react differently.”

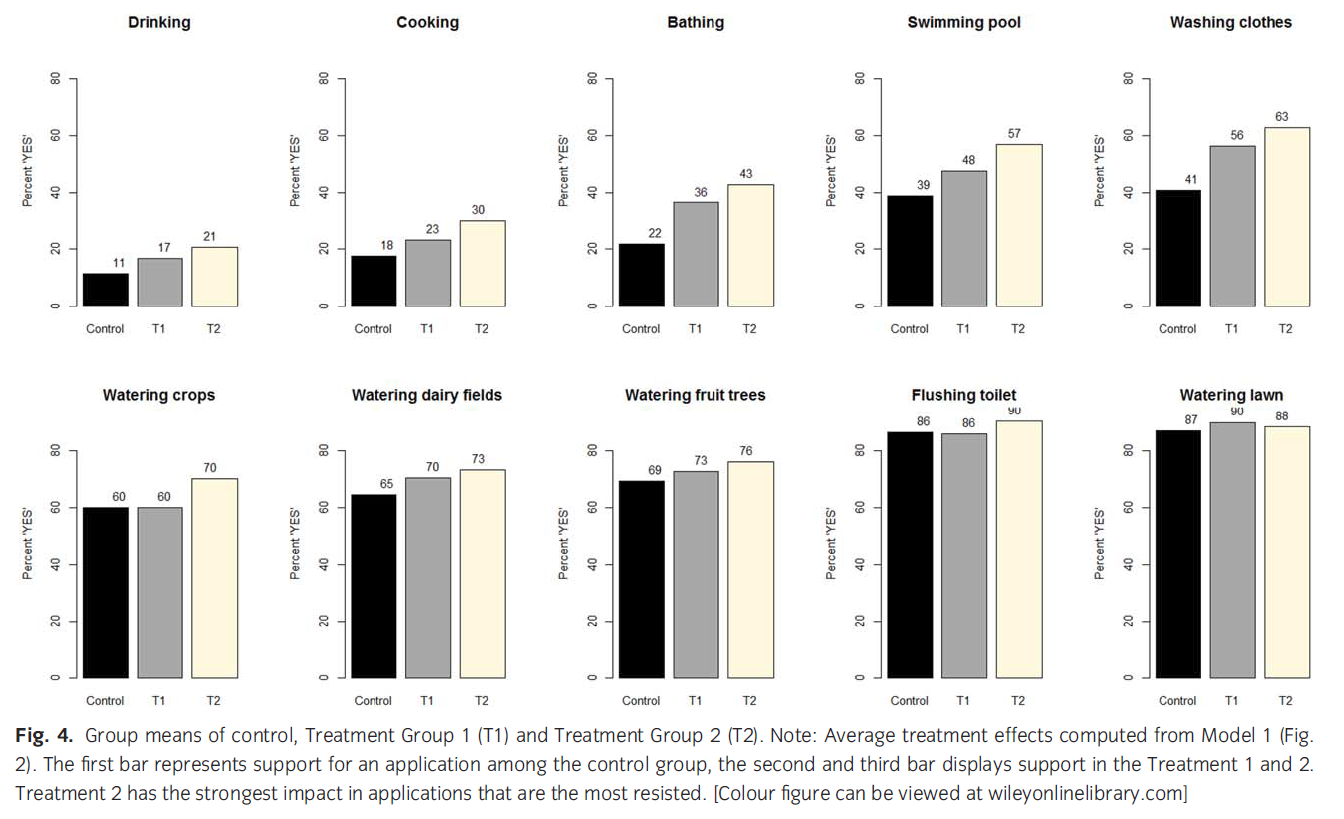

Although positive messages and explanations of the process made Californians more comfortable with using recycled water, there was still significant resistance to using treated wastewater for drinking and cooking. For example, willingness to drink recycled water increased from 11% to 17% after people were informed that Orange County has a “toilet to tap wastewater recycling program for outdoor and indoor water use, including drinking and bathing,” and that this system provides 70% of the county’s water. When the “toilet to tap” moniker was dropped and additional positive information was provided about the treatment process, support for using recycled water increased further, but the share of Californians willing to drink it was still only 21%.

The graphic below from the paper summarizes the impact of the educational messages. “T1” is the group that learned about Orange County’s “toilet to tap” system and “T2” is the group that received messages that dropped the “toilet to tap” phrase and included more information about the treatment technology.

Implications for water policy

The researchers argue that their findings have important implications for water policy, not only in California but also in other areas that are struggling to find new water sources:

- The existence of successful recycling programs appears to reassure people about the technology. “As more communities adopt recycled water without harmful effects, the resistance to recycled water in other communities may break down over time,” Hui and Cain write.

- The near-universal, instinctive aversion to recycled water “has the redeeming feature that lessons learned in one setting have a good chance of applying to other settings as well,” according to the study.

- While public outreach campaigns are essential for increasing public acceptance of recycled water in a variety of uses, the aversion to drinking recycled water remains strong even after people are educated about an existing program such as Orange County’s. “Our findings suggest that in arid communities that want to enhance their water supply with recycled water might have to deploy separate piping systems for potable and nonpotable uses,” Hui and Cain write.

Sources

- “Overcoming psychological resistance toward using recycled water in California,” by Iris Hui and Bruce Cain, Water and Environment Journal, August 2017.

- Frequently asked questions about Orange County’s Groundwater Replenishment System

- Our July 2017 post summarizing other polling on recycled water

WaterPolls.org aggregates, analyzes, and visualizes public opinion data on water-related issues. Stay informed via Twitter, Facebook, Pinterest, RSS, and email.